SJH

Shatter Your Entire View Of Health

Join others getting their entire idea of what health is shattered every Sunday while reading The Progress Letter.

May 21, 2023 | Max Jenkinson

The Dark Side Of Seed Oil Fat: Why It's Different & Why It's Bad For You

Picture this: almost half a decade ago, I stumbled upon the disturbing world of seed oils.

Determined to banish them from my diet forever, I embarked on a mission through the aisles of the supermarket.

What I discovered left me utterly astonished.

Seed oils seemed to lurk in almost every product with more than three ingredients.

Driven by my newfound knowledge, I decided to eliminate these oils from my life, and the results were nothing short of remarkable.

My sleep improved, my mood lifted, my skin glowed, my energy soared, and even my body composition underwent a positive transformation.

But here’s the catch: unless you’ve studied basic chemistry at a university level, chances are you’re in the dark about what fats truly are.

To comprehend the distinct nature of the fats found in seed oils, we must grasp some fundamental principles of chemistry—principles you’re already acquainted with.

When confronted with complex issues, we often require simple frameworks to gain a solid understanding.

As long as these frameworks surpass our current knowledge, they are undoubtedly worth exploring.

Today, we’ll embark on a journey together to construct a straightforward framework for comprehending fats.

By doing so, you’ll acquire a deeper understanding of why the fat in seed oils may be detrimental to your well-being.

Just as Huberman emphasizes, if we desire change, we must understand the mechanisms behind the actions we take.

To kickstart our exploration, we will gain a basic understanding of what fat is.

Then we will delve into three key aspects that set the fat in seed oils apart from the rest.

What is fat?

Fat is the word we use to describe lipids (substances that do not dissolve in water) that are solid at room temperature.

We use the word oil instead when describing lipids that are liquid at room temperature.

There are many different forms of lipids, and humans only use a few.

The vast majority that we get through diet are triglycerides. They contain one glycerol molecule and three fatty acid tails.

The fatty acids will be the focus of today’s post.

You can think of the fatty acids as carbon-hydrogen chains.

They have a length, defined by the number of carbon atoms.

They can be:

Short Chain- less than 6 carbon atoms

Medium Chain – between 6 & 12 carbon atoms.

Long Chain – 12 or more carbon atoms.

The fatty acids are also categorised by the number of double bonds in the carbon chain.

Here we have three categories that you have surely heard of:

Saturated fatty acids

Monounsaturated fatty acids

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

If you remember from chemistry, atoms “want” to have their outer shell filled with electrons.

Once its outer shell is full the atom is “satisfied”.

This is called the octet rule because the most familiar atoms can have eight electrons in their outer shell.

The carbon atom has 4 valence electrons. It would like to have 4 more.

It fills its outer shell by sharing electrons with other atoms.

In the case of saturated fatty acid, the carbon atom shares one electron each with hydrogen and other carbon atoms.

Once the carbon atom bonds with four other atoms it is sharing a total of eight electrons. It is now satisfied or saturated.

In a saturated fatty acid, all carbon atoms share electrons with four other atoms.

The carbon atom can also share two of its electrons with one other atom that also shares two of its electrons.

This is what we call a double bond.

This sharing is less perfect and so the carbon atoms are less satisfied, in other words, unsaturated.

If this less perfect sharing occurs at one position in the fatty acid chain, the fatty acid is monounsaturated.

If this occurs at two or more positions, we call the fatty acids polyunsaturated.

Pretty simple right?

The double bonds create a bend in the fatty acid chain. This is not shown in the graph because they wouldn’t fit neatly.

Fun fact:

This makes it harder to pack the fatty acids on top of each other.

This is why oils that are mostly unsaturated are liquid at room temperature.

And why fats like butter or coconut which are mostly saturated are solid at room temperature.

The more unsaturated the oil the colder it needs to get before it turns solid.

Moving on to the three aspects that make these oils especially damaging.

1 – Unsaturated, dissatisfied, fatty acids & their willingness to react

Now we understand the fundamental difference between fatty acids and the number of double bonds.

Unsaturated fatty acids are not “satisfied”, but they would like to be.

This is the big difference maker.

The dissatisfaction, chemically speaking, can be seen as a willingness to react.

The more dissatisfied an atom or molecule is the more likely it is to react with other atoms or molecules.

They can reach a more satisfied state by:

Giving away electrons

Stealing electrons

Sharing electron

This might be unintuitive but bear with me. The closer an atom is to filling its outer shell the more dissatisfied it is.

This can be seen as if the motivation to reach satisfaction increases the closer an atom gets to a full outer shell.

It is also dependent on the size of the atom, the smaller the atom the more the positively charged protons can pull in other electrons.

This is why fluoride which is a very small atom with seven valence electrons is the most reactive of them all.

We call the willingness to steal electrons, electronegativity, in other words, electron loving.

Oxygen is also a small atom but has six valence electrons instead, making it the second most electron-loving atom.

This is the reason we call free radicals, or reactive oxygen species, oxidants. Or, as Morely Robbins likes to call them, accidents with oxygen.

Oxidants are created naturally when we metabolise food. We can also get them through diet, radiation or pollution.

These atoms or molecules are so close to filling their outer shell that they are scavenging for other molecules to steal electrons from.

One of these is unsaturated fatty acids.

A saturated fatty acid is quite satisfied and would mostly like to be left alone.

An unsaturated fatty acid is slightly dissatisfied and would rather not have a double bond.

This makes it willing to react with other molecules in the hope of becoming more satisfied.

This willingness to react makes them potential victims of electron thieves (oxidants).

If an oxidant steals an electron from the unsaturated fatty acid it becomes angry and disappointed.

So angry that it wants to steal back an electron from someone else.

This creates a cascade effect causing an electron thief epidemic.

This in turn can cause damage to tissue, membrane and all the way down to the DNA.

To stop this cascade effect there needs to be enough police (antioxidants) to take care of the thieves (oxidants).

The antioxidant’s job is to make all parties satisfied.

2 – The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids

The polyunsaturated fatty acids come in different shapes and sizes.

You have probably heard of omega-3s and maybe even omega-6s.

As you now know, fatty acids are categorised in length.

The unsaturated fatty acids are categorised further into two more.

Position of the first double bond

The number of double bonds

The number after omega refers to where the first double bond is on in the carbon chain.

There are many positions where the first double bond can be.

Omega-3

Omega-6

Omega-7

Omega-9

But, only two of the polyunsaturated fatty acids are essential.

Meaning we cannot synthesise them ourselves and have to get them through diet.

These two are:

Alfa-linolenic acid (C18:3, omega-3)

Linoleic acid (C18:2, omega-6)

“C18” refers to the length of the chain (18 carbon atoms), and “:3” and “:2” refers to the number of double bonds.

Both are polyunsaturated which means they are dissatisfied and reactive.

They have somewhat opposite effects on the body.

The omega-3 fatty acids have an anti-inflammatory effect while the omega-6 fatty acids are inflammatory.

The body is in constant flux between inflammation and anti-inflammation.

This needs to be constantly regulated both systemically, and locally to maintain health.

This makes the ratio of omega-6:omega-3 particularly important.

If one consumes too much of either the balance becomes out of whack.

Evolutionarily this ratio seems to have been around 1:1 to 4:1. Today it is closer to 10:1 or even as high as 20:1.

In ruminants (red meat) the percentage of polyunsaturated fats is around 5% with the ratio being 2:1.

In nature, we find high concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids in nuts and seeds.

They are especially high in the inflammatory omega-6 fatty acids.

This is the reason why seed oils are usually extremely high in omega-6 fatty acids.

The seed oils are also often in a ratio that is far from 2:1 seen in ruminants.

A high ratio has been shown to be an excellent predictor of negative health outcomes.

And a reduction in the ratio has been shown to reduce or solve many types of disease.

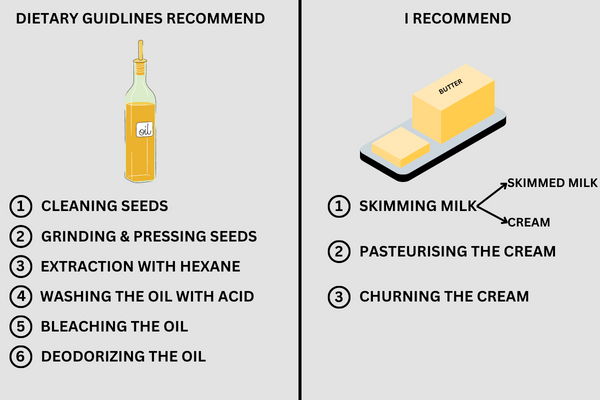

3 – They are industrially produced

By considering the first aspect you might be realizing that the ratio is not the only difference maker.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids are high in nuts and seeds.

The plants pack the vital seeds (and nuts, which are seeds) with antioxidants.

These antioxidants protect the seeds from an electron thief epidemic.

In other words, from oxidized polyunsaturated fatty acids.

In the first post in this series, you learnt that the liquid seed oils weren’t developed until the 40s because of a chemical fix.

The seeds are small and filled with reactive fatty acids making the extraction of the fats into an edible form difficult.

Innovation made seed oils possible.

So, we need to gain a grasp of the complicated extraction process.

Seed oils are produced in multiple steps.

In many of these steps, the oil is heated to 100°C all the way up to 250°C.

And as we know from chemistry, heat increases the likelihood of a reaction.

These reactive fatty acids are extremely heat sensitive.

Even though they are washed and dangerous byproducts are removed. To assume that they come out of this long process unscathed is naive.

The heating of these oils is the reason why many experts equate eating fried food with smoking.

We have now succeeded in producing neutral cooking oils through a long industrial process.

Oils that contain an unnatural amount of polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Oils that contain fatty acids in an unnatural ratio of omega-6:omega-3 which is believed to drive disease.

Oils that were highly reactive, heat sensitive and in need of their antioxidant friends even before they were extracted.

These are only three aspects that make seed oils especially harmful (there are many more).

Three mechanisms that could potentially make the seed oils detrimental to human health.

Yet, we can not be sure that these mechanisms will play out as we predict in a human biological system.

To find out if the seed oils act the same in the human body as they do in the chemistry lab we need to look at experimental data.

Controlled studies that aren’t based on questionnaires. Studies made in labs with concrete measurements.

On to the next post: What do the studies say?